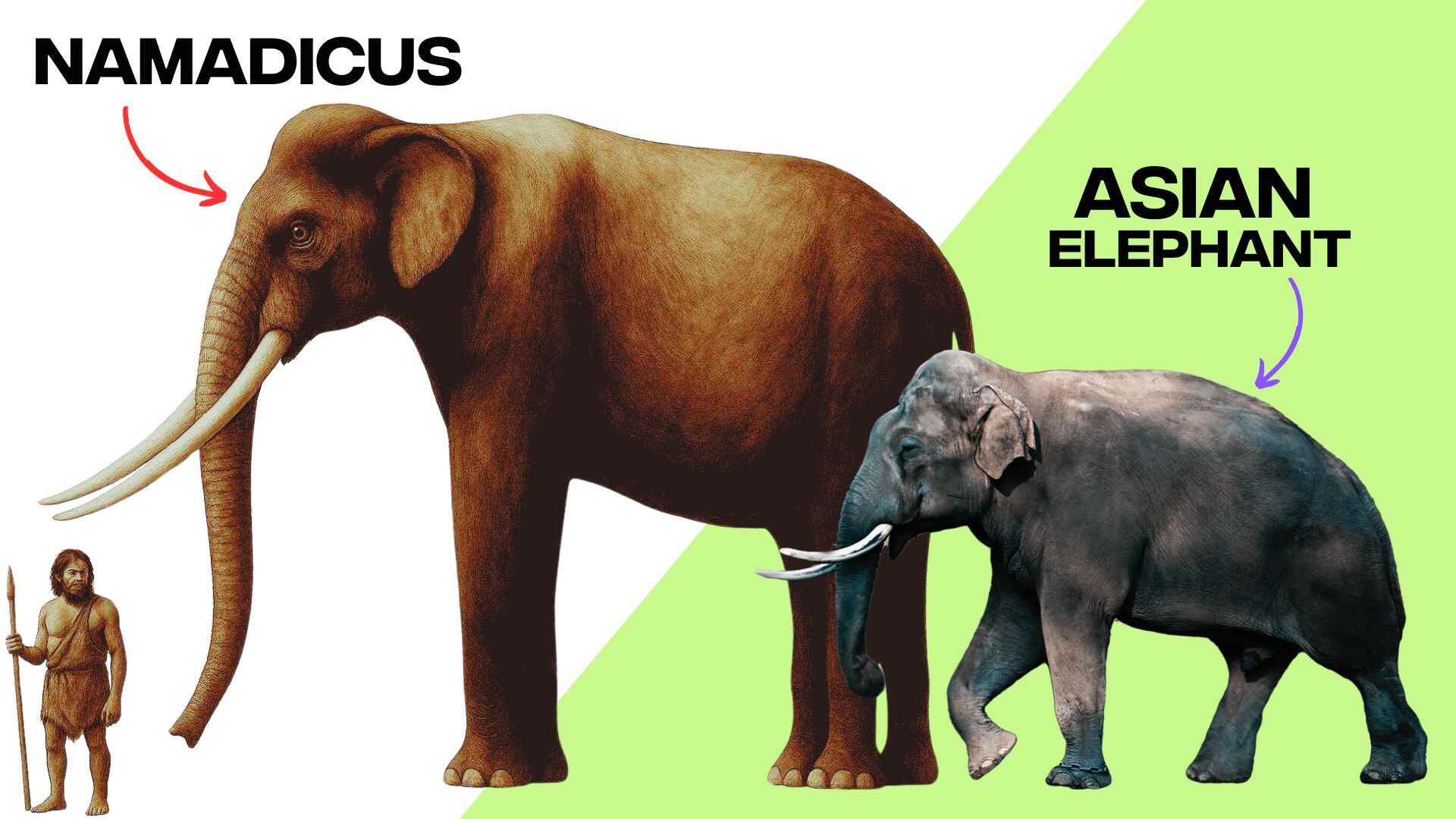

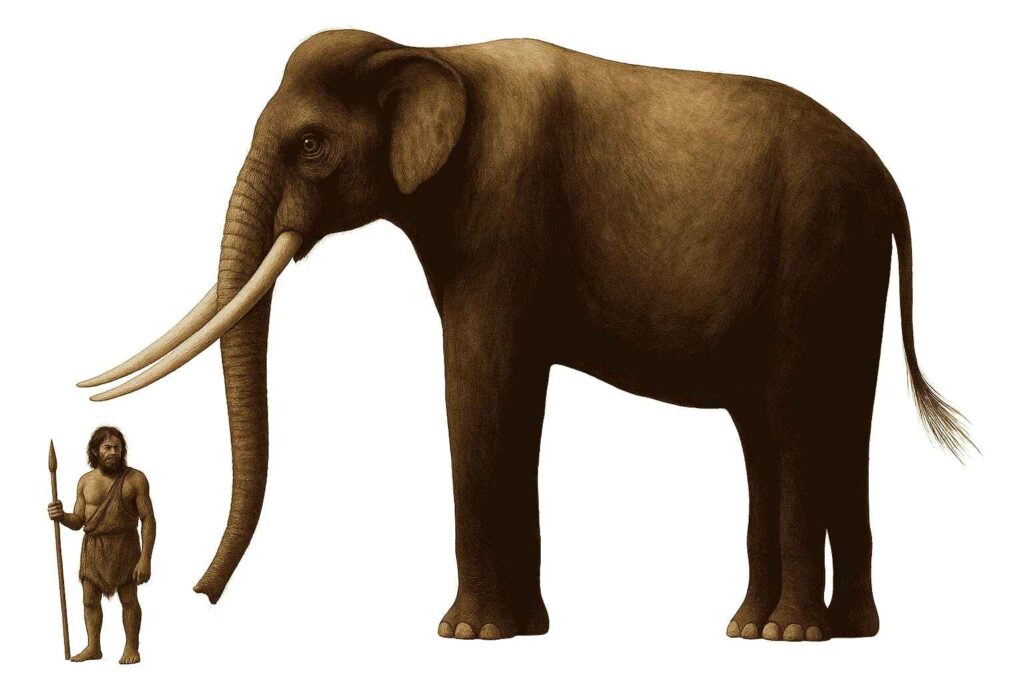

Imagine an elephant so massive that it would outweigh three Tyrannosaurus rex and stand taller than a two-story building. This wasn’t a creature of mythology but a real giant that once thundered across the Indian subcontinent. Palaeoloxodon namadicus, the Asian straight-tusked elephant, represents one of the most impressive land mammals ever to exist, with fossil evidence suggesting it may have been the largest land mammal to ever walk the Earth. Recent discoveries are shedding new light on these magnificent beasts and their interactions with our human ancestors, revealing a fascinating chapter in India’s prehistoric past.

The Giant Among Giants: Understanding Palaeoloxodon namadicus

Palaeoloxodon namadicus belonged to the genus Palaeoloxodon, a group of straight-tusked elephants that evolved in Africa around one million years ago before expanding into Eurasia. These elephants roamed the Indian subcontinent during the Middle to Late Pleistocene period, approximately 781,000 to 11,700 years ago. Although closely related to the European straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), P. namadicus is distinguishable by its stouter cranium and less robust limb bones.

What makes Palaeoloxodon namadicus particularly remarkable is its extraordinary size. While only known from partial remains, volumetric analysis of fossil limb bones suggests truly staggering proportions. Some specimens have been estimated to stand 4.5 meters (nearly 15 feet) at the shoulder, with the largest individuals potentially reaching heights of 5.2 meters (17 feet). Weight estimates for the largest specimens exceed 22 tons – comparable to many sauropod dinosaurs, outweighing Diplodocus carnegii and triple the weight of famous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex.

Physiological Adaptations

The bones of P. namadicus were much thicker and stronger than those of modern elephants, a necessity to support its immense weight. Its legs were more heavily built with thicker and longer bones to handle the increased stresses of locomotion at such a size. Like modern elephants, Palaeoloxodon couldn’t run (defined as having all four limbs off the ground during stride), but its long stride would have allowed it to cover significant distances.

A particularly distinctive feature was the massive, headband-like crest on the skull roof that projected down the forehead. This feature was so pronounced that when Scottish geologist Hugh Falconer first studied a fossil skull from India, he remarked that it looked like “the caricature of an elephant’s head in a periwig.” This crest developed throughout the elephant’s lifetime, becoming larger and more prominent as the animal matured.

Discovery and Early Research in India

The story of Palaeoloxodon namadicus in scientific literature begins during the rule of the British East India Company in the 1830s. Remains now recognized as belonging to this species were unearthed as early as 1834, when a remarkable 1600mm femur was discovered in Sagauni, suggesting an individual that would have weighed approximately 13 tons despite not being fully grown.

The species was formally named as Elephas namadicus by British paleontologists Hugh Falconer and Proby Cautley in 1846, based on a skull collected from the valley of the Godavari River in central India. The name “namadicus” derives from “Namadus,” the Greek name for the Narmada River, where many significant fossils were discovered.

For decades, knowledge of this species remained fragmentary. In 1905, a partial skeleton found in the Godavari River was described, with an estimated shoulder height of 4.5 meters. Through the early 20th century, various taxonomic reclassifications occurred. In 1924, Japanese paleontologist Matsumoto Hikoshichirō placed the species within his newly coined subgenus Palaeoloxodon, and by 1942, American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn elevated Palaeoloxodon to genus status, creating the current classification.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat

Palaeoloxodon namadicus fossils have been found across several key regions in the Indian subcontinent:

- Narmada River Valley – The eponymous location where many of the first fossils were discovered and the species was named.

- Godavari River Valley – Site of significant skeletal discoveries, including the skull used in the original species description by Falconer and Cautley.

- Kashmir Valley – Location of more recent discoveries, including a remarkably preserved skull found alongside stone tools.

Beyond India, potential evidence of P. namadicus has been found in other Asian locations including China, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, suggesting a wide distribution across subtropical and temperate Asia. These giant elephants appear to have preferred temperate, wooded habitats, though their exact ecological niche is still being studied.

The Kashmir Valley Discovery: Evidence of Human Interaction

One of the most significant recent developments in our understanding of Palaeoloxodon in India came in 2000, when an extraordinary fossil discovery was made near the town of Pampore in the Kashmir Valley. A team of geologists led by Drs. AM Dar, MS Lone, Ghulam Bhat, and veterinarian MS Shalla unearthed a remarkably complete elephant skull alongside 87 prehistoric stone tools.

The skull was massive – standing 1.37 meters tall from the skull roof to the base of the tusk sheaths – and belonged to an animal estimated to have stood 4 meters tall and weighed approximately 13 tonnes. Scientific analysis didn’t occur until 2019, when researcher Advait Jukar joined an international team to examine these remains.

The discovery was groundbreaking for two reasons. First, it represented the most complete Palaeoloxodon skull ever found in India. Second, it provided the earliest evidence of animal butchery in the Indian subcontinent, dating to between 300,000 and 400,000 years ago.

Careful examination revealed that the elephant bones showed signs of breakage likely caused by repeated blows from stone tools, suggesting early humans were extracting bone marrow from these megaherbivores. The stone tools, made from basalt not found in the immediate area, were apparently transported to the site specifically for processing the elephant remains.

Interestingly, detailed morphological analysis of the Kashmir skull suggests it may not have belonged to P. namadicus but rather to P. turkmenicus, a related species previously known only from fragmentary remains in Turkmenistan. This finding adds complexity to our understanding of Palaeoloxodon evolution and distribution across Asia.

Extinction and Coexistence with Humans

The story of Palaeoloxodon namadicus in India also provides intriguing insights into the relationship between megafauna and humans. Recent research suggests that the extinction of P. namadicus began around 30,000 years ago – approximately 30,000 years after modern humans arrived in the Indian subcontinent.

This timeline is significant because India and Africa show similar patterns of low-magnitude extinctions of megafauna, in contrast to the more severe extinction events in places like North America, Europe, and Australia. This supports the “co-evolution hypothesis,” which suggests that the magnitude of an extinction correlates with the amount of time that large mammals coexist with humans and their ancestors.

The first hominins arrived in India approximately 1.7 to 1.5 million years ago, meaning that megafauna like P. namadicus had a long period of coexistence and potential adaptation to human presence. This extended coevolution may explain why some large mammals in India, like elephants and tigers, have persisted while many of their counterparts elsewhere went extinct.

Evolutionary Significance

The Palaeoloxodon genus first appears in the fossil record in Pliocene Africa around 3.5 million years ago as Palaeoloxodon recki, a massive species estimated to have weighed upwards of 15 tons. Before going extinct in Africa around 130,000 years ago, members of this genus migrated into Eurasia, diversifying into several different species.

The evolutionary relationship between various Palaeoloxodon species has been debated. Some researchers have historically considered P. namadicus and the European P. antiquus to be the same species due to similarities in skull and tooth morphology, though they are now generally considered distinct.

Recent studies of skull development across Palaeoloxodon specimens from Italy, Germany, and India have shed light on how these animals matured, with the distinctive skull crest developing from minimal prominence in juveniles to being large and protruding in adults.

A Lost Giant of Ancient India

Palaeoloxodon namadicus represents one of the most magnificent lost giants of India’s prehistoric past. From the Narmada and Godavari river valleys to the Kashmir highlands, these colossal elephants once dominated the landscape of the subcontinent. Their discovery and continued study offer valuable insights not only into elephant evolution but also into the complex relationship between humans and megafauna throughout prehistory.

As research continues, particularly on remarkable specimens like the Kashmir skull, we can expect to learn even more about these extraordinary animals that once called India home. Their legacy enriches our understanding of India’s natural history and highlights the remarkable diversity of life that has inhabited the subcontinent over hundreds of thousands of years.